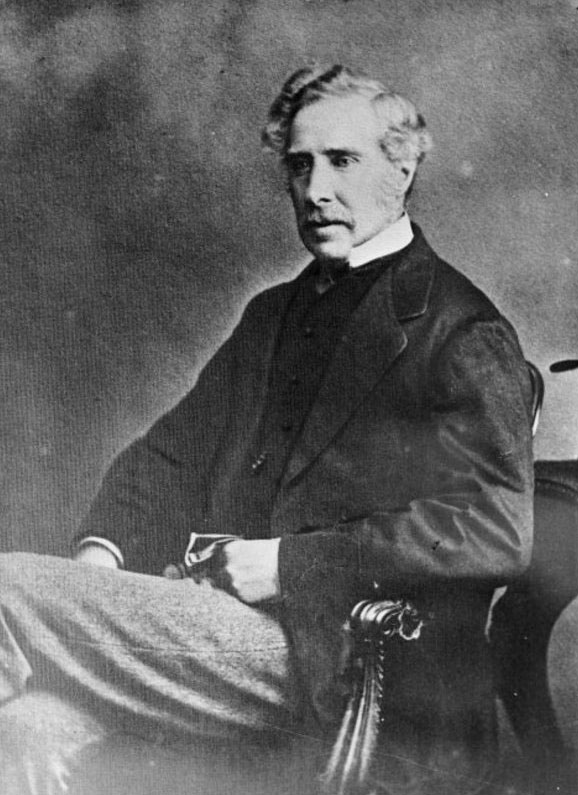

George Grey

Governor: intelligent, ambitious, ruthless

Born 14 April 1812

Died 17 September 1898

Spouse Eliza Lucy Spencer

Children One son, lived only five months

Early Years

Grey was born in Lisbon, Portugal, into a military family. His father was killed just eight days before his birth during a particularly bloody episode of the Napoleonic Wars. As a child, Grey was sent to an English boarding school and after that he attended Sandhurst, the prestigious military college. Upon his graduation, he was commissioned an ensign in the army and sent to Ireland with his regiment. Grey’s experience of the poverty and misery of the Irish people convinced him of the merits of emigration to the colonies.

Australia

In 1836, Grey went to Australia. Adventurous and ambitions, he had arranged to explore parts of Western Australia in the hopes of finding suitable land for a settlement. His expeditions were disastrous, but he was nevertheless appointed resident magistrate at King George Sound a few years later.

Australian aboriginal culture was of great interest to Grey and he began to develop theories about assimilating and “civilising” indigenous peoples. When he became Governor of South Australia in 1840, his theories proved impossible in practice. Violence on both sides continued, and his schools for Aboriginal children were a failure. Grey did succeed in balancing the books by ruthlessly cutting expenditure.

Governor of New Zealand

On 14 November 1845, Grey arrived in New Zealand to replace Robert Fitzroy as governor. It was a delicate time: the war against Heke and Kawiti was not going well for the British, and the economy was in a very poor state. Fitzroy had been working on a peace deal with the “rebel” chiefs, but Grey promptly issued an ultimatum with an unreasonably tight timeframe: accept the current terms at once or hostilities would resume.

Grey displayed his excellent skills as a propagandist after the Battle of Ruapekapeka. He was present during the battle and so he knew the truth behind Colonel Despard’s account of an overwhelming victory. In the months that followed, Grey worked hard to generate and perpetuate the myth that that British won the Northern War. He wrote that “the rebel Chiefs had been defeated and dispersed” and that Heke and Kawiti had “made their complete submission to the Government.” The reality was that he could not afford for the Northern War to continue. There were rumblings of discontent from Māori in Wellington and Wanganui, and Grey did not have the resources to fight two wars at once. Even worse was the thought of a general uprising of Māori across the country.

After Ruapekapeka, Grey did not enforce any punitive measures against Heke and Kawiti. He basically decided to leave the north alone. This approach was in sharp contrast to his pre-battle rhetoric, that it would be “absolutely necessary to crush either Heke or Kawiti before tranquillity could be restored to the country”. Excellent spin-doctor that he was, he framed his about-face as an act of clemency.

Grey served as Governor of New Zealand until 1853 and again from 1860 until 1868. During his first term, he had far greater resources than predecessor (three times the funding and twice the salary) and by some measures he did quite a good job. He appeared to honour the terms of the Treaty of Waitangi, but at the same time, he convinced many Māori to part with large tracts of land. Echoing his experience in Australia, his efforts to ‘civilise’ Māori were not very successful. His relations with European settlers were not harmonious, due in part to his reluctance to establish an elected government. In fact, he was personally inclined towards democracy, but he could see that the system proposed by the settlers was extremely unfair to Māori. Grey eventually did write a constitution for New Zealand, setting up provincial and central representative assemblies.

In 1853, Grey left New Zealand to become the governor of the Cape Colony and high commissioner for South Africa. Race relations were again a problem and there were frequent outbreaks of violence. On a personal note, Grey’s relationship with his wife Eliza was faltering. She accused him of repeated infidelity and was herself involved in an extramarital romance. The two lived apart for the following 36 years. At the same time, Grey’s professional relationship with the Colonial Office was becoming strained.

Grey’s second stint as governor of New Zealand began in 1860 as strife broke out in the Taraniki region. He hoped to smooth over the situation, but he did not succeed. Grey was at the helm during the second phase of the New Zealand Wars, with widespread fighting in the central North Island. In the aftermath, Grey agreed to massive land confiscations – three million acres – from the “rebel” chiefs. His time as Governor of New Zealand ended on a sour note. The British Government had decided to withdraw imperial troops from the colony, an instruction that Grey failed to implement. His appointment as governor was terminated in 1868.

After his termination, Grey went to England for a short while, but shortly returned to his mansion on Kawau Island in the Hauraki Gulf. His involvement in New Zealand politics was not over: he served as superintendent of Auckland province and was elected to parliament. By October 1877, he had clawed his way back to the top, and served as premier for several years.

Later Years

Grey’s later years were colourful and eventful. As a back-bencher in Parliament he was radical and outspoken, making quite a few enemies in the process. He devoted some time to his life-long interest in naturalism and he wrote books about Māori language and culture. In 1893, he left New Zealand for the last time, to live out his final years in England. He reunited with his estranged wife in 1897, one year before his death. Grey is remembered as a complicated and interesting character and a key figure in early New Zealand politics.