Hōne Heke

Hōne Heke’s name will forever be synonymous with the Northern War. With his persuasive and charismatic personality, he wielded considerable influence. He convinced other powerful Northern chiefs to stand beside him and defend the rights of Ngāpuhi. However, he was also something of a divisive figure, and some Māori chiefs chose to take up arms against him.

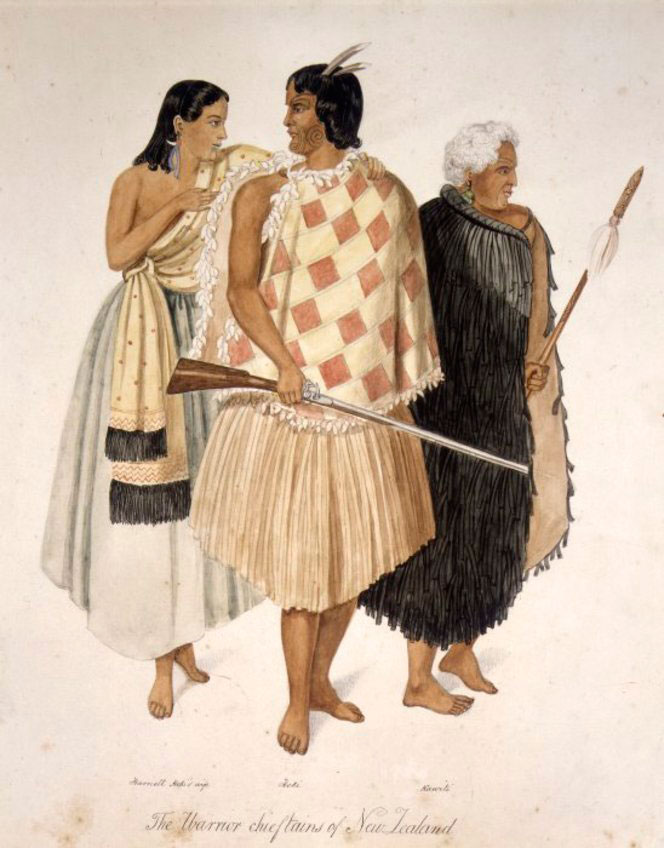

Ngapuhi warrior chief: charismatic, fiery, intelligent

Born 1807

Died 6 August 1850

Spouse Hariata Rongo (daughter of the great Hongi Hika)

Early Background

Heke was born in 1807 in Pakaraka in the Bay of Islands and he attended the mission school in Kerikeri. The missionaries found him an intelligent and troublesome child. He grew into an imposing figure, six feet tall and well-built. During the upheaval of the 1830s, Heke made a name for himself as a warrior. When he married Hariata Rongo, the daughter of the great chief Hongi Hiki, his status was further enhanced. By 1840 (the year of the Treaty of Waitangi) Hōne Heke was an influential leader.

Heke and Te Tiriti

Heke started out as a supporter of The Treaty/Te Tiriti. He stood and spoke at the Waitangi hui, and helped to shift the general mood of the meeting in favour of signing Te Tiriti. He was probably the first Māori chief to sign the document.

Within a few years, Heke was disillusioned and angry. In his eyes, the British were not honouring the terms of the agreement he facilitated. At first, his reaction was peaceful and restrained: he wrote letters and discussed his concerns with missionaries and officials, but to no avail. By 1844, he was deeply concerned about the continued erosion of Ngāpuhi mana and chiefly authority. Fully aware of its symbolic importance, he cut down the flagstaff at Kororāreka, an act which forced the authorities to pay attention.

The War in the North

Heke persisted with his attacks against the flagstaff, culminating in March 1845 with the destruction of the town of Kororāreka. Heke and his allies had not planned to destroy the town. They intended only to engage the British troops long enough to cut down the flagstaff for the fourth time. However, the British took Heke’s actions to be a declaration of war.

In May that year, Heke and the venerable Te Ruki Kawiti forced the British to withdraw at the Battle of Puketutu. During that engagement, Heke and his men were stationed within the pā, while Kawiti’s forces engaged the troops outside. Heke provided covering fire and at one point, he sallied from the pā to allow Kawiti time to re-group.

Heke’s next military engagement was a great disaster. He attacked Tāmiti Wāka Nene at Te Ahuahu and suffered a decisive defeat. Many of his men were killed and Heke himself was gravely wounded. His men managed to transport him to safety, and he spent many months recovering, unable to participate in the action. He missed the Battle of Ohaeawai at the end of June 1845, just a few weeks after his defeat at Te Ahuahu.

During the lead up to the Battle of Ruapekapeka, Heke remained at Hikurangi tending food crops. He had arranged to join Kawiti when the soldiers began their attack, but the British sought to stop this from happening. Governor Grey contacted a local chief aligned with the Crown, asking him to prevent Heke from reinforcing Kawiti at Ruapekapeka. Heke and his taua finally did arrive at Ruapekapeka, only two days before the British gained possession of the pā.

Later Years

Heke’s mana and authority increased after the Northern War drew to a close, and he lived out the rest of his life relatively free from British interference. He passed away on 6 August 1850 from tuberculosis. Claim and counterclaim were made for his body. The missionary Richard Davis, who had given him spiritual support in the last months of his life, made a request for a Christian burial but was refused. He was allowed to read parts of the funeral service, before the body was taken away. Hōne Heke was buried in secrecy in a burial ground called Kaungarapa, where he joined notable tribal leaders of the past.