Hōne Heke

and the Flagstaff

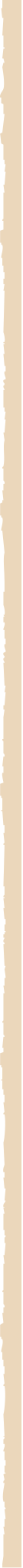

On 8 July, Hōne Heke cut down the flagstaff on Maiki Hill above Kororāreka (Russell) for the first time. Originally donated by Heke, the flagstaff was intended to fly the flag of the United Tribes of New Zealand. The British shifted it from Waitangi to Kororāreka to fly a different flag.

Depiction of Hone Heke cutting down the flagstaff at Kororārkea.

By A. D. McCormick. From the Alexander Turnbull Library ref. A-004-037

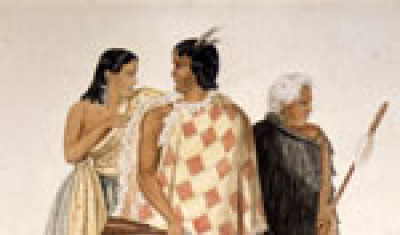

Robert Fiztroy, Governor of New Zealand from 1843 – 1845.

Photograph of an original portrait. From the Alexander Turnbull Library ref. 1/1-001318-G

Tāmiti Wāka Nene, a prominent Ngāpuhi chief who disagreed with the actions of Hone Heke.

From a painting by M. Matthews. From the Alexander Turnbull Library ref. 1/1-003858-G

Cutting it down was a highly symbolic act, reflecting Heke’s unhappiness with the reality of British sovereignty. To him, the British ensign flying high above Kororāreka (on his flagstaff) reflected the loss of Māori mana.

After the flagstaff fell, Heke and other prominent rangatira reached out to Governor Fitzroy (Governor Hobson had died suddenly a few years earlier). Heke offered to erect a new flagstaff and urged Fitzroy not to send any soldiers. Fitzroy ignored the offer and ordered British officials to re-erect the flagstaff without discussion. This was a grave insult to Ngāpuhi and to Hōne Heke in particular.

Fitzroy had no particular desire to go to war with Heke. He did not have a warlike nature, and the colony’s meagre resources were stretched to the limit as it was. However, the British flag was sacrosanct and the matter of the flagstaff was non-negotiable. Fitzroy wrote to the authorities in New South Wales requesting military support. Nearly 200 soldiers from Sydney were sent to Northland to protect the flagstaff and to “restore tranquillity”.1 Māori reacted with indignation because soldiers represented a blow to chiefly mana and Ngāpuhi authority.

Fitzroy was prepared to talk matters over in person. He travelled to the Bay of Islands in late August and attended a hui at Waimate, organised by several influential missionaries. Heke, deeply offended by Fitzroy’s earlier lack of communication, did not make an appearance at the hui. However many important Ngāpuhi rangatira did attend, determined to maintain the peace and to persuade Fitzroy to send the soldiers away.

The hui had a significant outcome, which explains in part how some Ngāpuhi ended up fighting alongside the British in the war that followed. Basically, a group of chiefs led by Tamāti Wāka Nene vouched for Heke’s good behaviour. They promised to keep Heke under control, on the condition that the soldiers were withdrawn from the north. They also agreed to pay utu for Heke’s actions. This was a final attempt to keep the peace and to prevent an armed invasion of Northland by all means necessary.

Relationships between the British settlers and Ngāpuhi continued to deteriorate after the Waimate hui. New arrivals were less likely to respect Māori authority, and more likely to infringe upon traditional laws or offend an important chief. Māori meted out traditional forms of justice such as the taua muru, loosely equivalent to a court-imposed fine. A party of warriors would descend upon the property of the offender, yelling and brandishing their weapons. The intention wasn’t to injure anybody – it was to seize possessions to compensate for the offence committed. That said, taua muru must have been absolutely terrifying to a recently arrived settler!

The pole that was cut down belonged to me. I made it for the Native flag and it was never paid for by the Europeans.

Hone Heke, Letter to Governor Fitzroy, July 1844

The situation continued to deteriorate for the remainder of 1844, and the Governor refused Heke’s request for a meeting. On 10 January 1845 Hone Heke chopped down the flagstaff for the second time, an act which demanded Fitzroy’s attention. He issued a bounty of 100 pounds for Heke’s capture and sent a group of soldiers to Kororārkea aboard the brig Victoria. Heke’s actions also caused the political rift between the factions of Ngāpuhi to widen. After all, Tamāti Wāka Nene and others had vouched for Heke’s good behaviour. Some were becoming concerned about Heke’s motives: was he trying to extend his chiefly authority, to raise himself above all others?

The flagstaff was soon re-erected by the soldiers, but it was to stand for less than a day before Heke cut it down again. Governor Fitzroy resolved to quell the challenges to British authority by force. He began to prepare for conflict, sending to Australia for troops and naval support. The soldiers built a blockhouse on Maiki Hill (Kororārkea) next to the flagstaff and surrounded both with sturdy wooden palisades. The redcoats were made ready to fight for the symbol of British sovereignty.

Meanwhile, Heke had been gathering support from around Northland. Early in 1845, he sent a message to Te Ruki Kawiti, the distinguished warrior chief of Ngāti Hine. Heke sent to Kawiti a beautiful greenstone mere smeared with human excrement. This was no ordinary weapon. It was a named taonga with great mana, handed down from Hongi Hika. The message was clear: Ngāpuhi mana, honour and authority had been trampled by the British. Heke was asking for help, and Kawiti agreed to join with him.

Heke’s fourth attack upon the flagstaff was to have dire consequences for the town of Kororārkea, and was the event, which marked the beginning of the Northern War.