Northland in

the Early 1800's

Few Europeans resided in New Zealand before 1840. There was about 1400 of them living in the entire North Island, a large proportion in the Northland region. They came from diverse backgrounds. There were the adventurers and opportunists, traders, a few convicts escaped from Australia, and missionaries with wives and children in tow.

Kororāreka in 1835/6 showing European houses, Māori houses, gardens, waka (canoes) and other boats.

By J. S. Polack. From the Alexander Turnbull Library ref. PUBL-0115-1-front

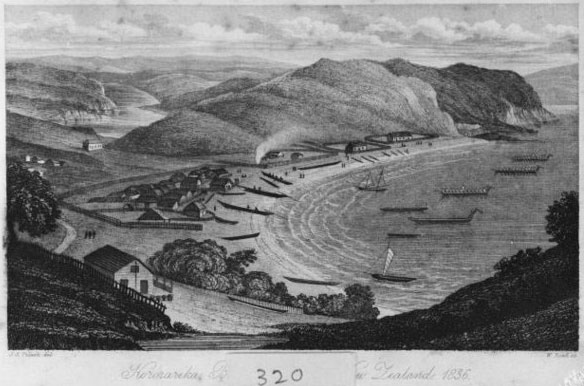

Kororāreka in 1838 showing pākehā men shifting barrels and working on a sailboat.

By T. R. G. Mesnard. From the Alexander Turnbull Library ref. A-234-010

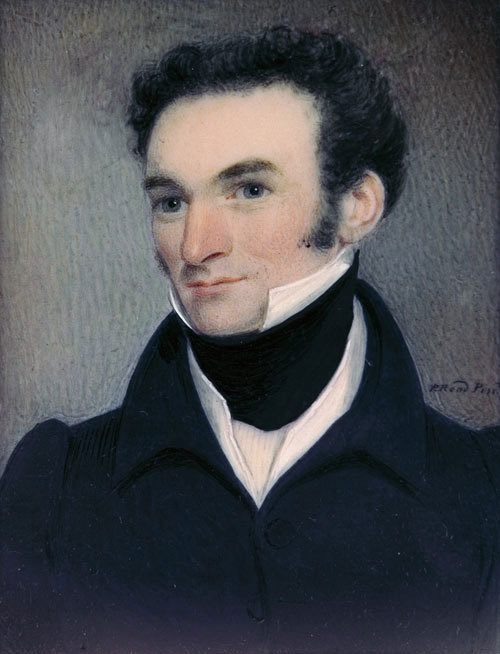

James Busby, British Resident.

By R. Read. From the Alexander Turnbull Library ref. NON-ATL-P-0065

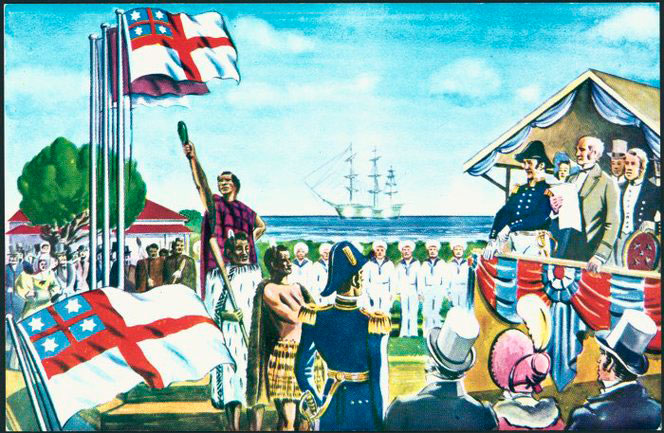

A 20th-century depiction of the flag of the United Tribes. James Busby and Māori chiefs and dignitaries are shown. The ship is the HMS Alligator.

Shaw Savill Line postcard Alexander Turnbull Library ref. 82-419-01

For a start, Ngāpuhi welcomed or at least tolerated a European presence in Northland. Of course, there were misunderstandings and the occasional violent incident. For the most part, however, maintaining friendly relationships was beneficial to all. The foreigners depended upon the goodwill of their Māori neighbours, who were themselves pleased to gain access to valuable European trade goods. Some of the early European residents formed relationships with local women and became fully incorporated into Māori society.

Although few Europeans settled in New Zealand in the early years, there was an exponential increase in the numbers of visiting ships. Many were whalers seeking whale oil to illuminate and lubricate the industrial revolution, and whalebone to make corsets for fine ladies. In the 1830s, something like 1000 ships visited New Zealand every year. Māori offered fresh food, timber and flax in exchange for an array of manufactured goods, including muskets, fabric, fishhooks and metal tools.

The missionaries played an important role in the early days. They functioned as intermediaries and translators, they taught literacy and European farming practices. Many Māori did convert to Christianity – nominally at least – blending the missionaries’ teachings with traditional Māori beliefs.

Māori society adapted to take advantage of new opportunities. This was especially the case in the Bay of Islands, a focal point of early European activity. Rangatira who were able to monopolise European trade became more powerful and their mana increased. Many Māori people became involved, harvesting timber, growing vegetables, and rearing pigs for their European customers.

Differential access to muskets altered the balance of power between different iwi with dramatic consequences. The inter-iwi Musket Wars were brutal and protracted, killing perhaps 20,000 people and displacing countless others. The wars did not end until the 1830s when other iwi acquired muskets of their own, and the balance of power was restored.

As well as altering the Māori economy, the flood of European trade goods had a profound effect on Māori warfare. Differential access to muskets altered the balance of power between different iwi with dramatic consequences. Ngāpuhi were the first to obtain a large number of muskets, which they put to good use against their enemies of old. The inter-iwi Musket Wars were brutal and protracted, killing perhaps 20,000 people1 and displacing countless others. The wars did not end until the 1830s when other iwi acquired muskets of their own, and the balance of power was restored.

During the 1830s, officials in Britain were becoming worried about the situation in New Zealand. There was no way to control unscrupulous sailors and traders, like the crew of the Elizabeth who facilitated a massacre. There were stories of ships recruiting Māori crewmen, who were then mistreated, unpaid and abandoned far from home. Furthermore, competition and violence between iwi was detrimental to European commercial ventures.

The Colonial Office intervened in 1832 with the appointment of James Busby as British Resident. Busby functioned as an intermediary and sought to encourage Ngāpuhi towards a more stable form of government. Busby convinced the northern chiefs to band together and to select a flag to represent the “United Tribes”. Shortly after, he put together a Declaration of Independence for the chiefs to sign (He Whakaputanga o te Rangatiratanga o Nū Tīrene). Although under the protection of Britain, the chiefly authority of Māori over their own lands was as yet undisputed.

1 This figure is an estimate provided by James Belich (1996:157)