Henry Despard

There is no known photograph of Henry Despard

Colonel: prejudiced, old fashioned, incompetent?Born c. 1784 (Ireland)

Died 30 April 1859, Devon, England

Spouse Anne Rushworth (m.1824)

Children Unknown

Early Years

Henry Despard was born in Ireland in 1784 or 1785. Joining the military must have seemed like a natural progression for young Henry as his father and most of his uncles were in the armed services. Unfortunately, one of his uncles was convicted of treason for leading an Irish uprising, and was the last man England sentenced to be hanged, drawn, and quartered.1 Despite the besmirched family name, Henry rose through the ranks of the British Army and retiring as a Major General.

Military Service

At 14 years of age, Henry became an ensign in the 17th Regiment on Foot. As a young man, he was stationed in India, fighting several campaigns and earning a promotion to Brigade Major in 1817. By 1829, he was a Lieutenant Colonel. By this stage, the British military had no significant wars to fight, so there was a shortage of jobs for career soldiers like Despard. He worked as the Inspecting Officer of the Bristol recruiting district for several years.

In 1842, Henry Despard made his way to Australia to take up the command of the 99th Lanarkshire Regiment on Foot. His regiment was stationed in Sydney on convict guard duty. In Sydney Despard’s true character was exposed: upon arrival, he immediately made himself unpopular by refusing to attend a ball thrown in his honour. He also refused to adopt modern drill methods, insisting on maintaining old-fashioned techniques, which caused chaos on the parade ground.

New Zealand

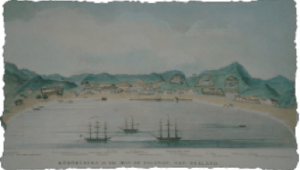

Despard arrived in New Zealand on 1 June 1845 to support Governor Fitzroy in his efforts to quell the Ngāpuhi “revolt”. Despite a formidable reputation, Despard was a man approaching old age who hadn’t seen active combat for almost 30 years. A painful case of gout did not improve his temper.2 He took command of all of the British troops stationed in New Zealand. Within a week, Despard and a large contingent of men were sailing to the Bay of Islands. The objective was Ohaeawai Pā, the current base-camp of the Ngāpuhi leaders Te Ruki Kawiti and Hone Heke.

The troops set up camp at the Waimate Mission Station to prepare for the march inland. Not long after their arrival Wāka Nene, an allied Māori chief, paid Despard a visit to offer his assistance. Despard’s scathing reply revealed his prejudiced views: “When I want the help of savages I will ask for it.” Fortunately, (for the British cause) this response was not translated back to Wāka Nene.

The Battle of Ohaeawai was a terrible disaster for the British. On 24 June, Despard opened fire upon the pa with his small brass cannons and 12-pounder carronades. A week later a massive 32-pounder cannon arrived on site. The defences were very strong and cleverly designed, and to start with the bombardment had little effect. On 1 July, some warriors conducted a daring sortie from the pa and briefly captured the 32-pounder cannon. They were soon driven back into the pa, but they took with them the Union Jack which had been flying on the flagpole above the position. Soon, the Union Jack was fluttering on the flagpole inside the pa, underneath the flag of Kawiti and Heke.

Despard made a dreadful decision. Against all advice, he ordered a direct assault even though the palisades had not been breached. The attack made little sense in terms of proper military tactics, and it seems that Despard was motivated by a fit of ill temper more than anything else. The troops were ordered to cut down the palisades or to scale them with ladders, tasks that proved impossible. The defenders, safely behind the palisades, opened fire at the mass of British troops and within minutes more than 100 lay dead or wounded. Despard was distraught.

"Despard watched the carnage with horror and amazement. In the frenzy of his despair, he lost his self control. He ordered the bugle to sound ‘retreat’, and immediately afterwards demanded to know who had given the order. “You yourself, Sir, did this very minute”, answered Ensign Symonds”.3

Despard tried to blame the disaster on his troops (many of whom were dead) for failing to carry ladders and axes with them as ordered. However, he did concede at a later date that the attack had little chance of success, given the strength of the outer defences.

The officers, the troops, contemporary newspaper reporters, and virtually every historian who has since written about the battle have attributed the outcome to Despard’s extreme incompetence. However, James Belich, the revisionist historian, makes an interesting point about Henry Despard and the role of Victorian racial stereotypes. Rather than admire the intelligence and skill of the Ngāpuhi defenders, it was easier to blame stupidity of the British commander. How else could a handful of “savages” defeat 600 of the finest British troops?

Ruapekapeka

Peace negations were put aside when George Grey, the new Governor, arrived in late 1845. Despard was ordered to attack Kawiti’s new stronghold: Ruapekapeka Pā. With twice the number of troops than at Ohaeawai and substantial artillery support, Despard marched inland.

Despard exercised a great deal more care and caution and avoided many of the mistakes of Ohaeawai. He concentrating his fire at specific points along the defences and fired shots throughout the night so that repairs could not be made. His tactics proved successful and ten days later the defences were breached. However, Despard again demonstrated his poor judgement. Despite the horrible experience of Ohaeawai he almost carried out a premature assault upon Ruapekapeka Pā. In this instance, Despard actually listened to the advice of his Māori allies and called off the assault until the following day. Had he not, it is likely that a great many more British troops would have lost their lives.

In his post-battle report, Despard stretched the truth and claimed that Ruapekapeka Pā had been taken by assault. (In fact, the troops had found the pa to be virtually empty, because Kawiti and his men were in the process of an orderly and planned withdrawal). If Ruapekapeka was a victory for the British, it certainly was a hollow one. The British Government were in need of any kind of victory at all, and so Despard’s version of events was perpetuated.

After the Northern War

The Northern War drew to a close after the Battle of Ruapekapeka and Despard was sent to New South Wales. Soon afterwards, he was appointed a Commander of the Order of Bath, a highly prestigious order of chivalry. In light of this, it is possible that stories of Despard’s incompetence have been exaggerated. However, the standard interpretation is that Henry Despard was unfit to command the British Troops during the Northern War. A product of the Napoleonic era, he was too old-fashioned, too inflexible, too prejudiced and too impatient.

Despard retired from the army in 1854 at the rank of Major General, and died five years later in Devon, England.

1 his sentence was commuted to a simple hanging and beheading