Tāmiti Wāka Nene

Tāmiti Wāka Nene was a diplomat, a peace-maker, a war leader and respected Rangitira of the Ngāpuhi iwi. During the Northern War he supported the British and fought against Heke and Kawiti. His reasons for aligning his people with the Crown reflected a political rift between factions of Ngāpuhi. To this day, Nene’s actions are a delicate subject among Northern Māori. Some feel that he betrayed his own people by fighting alongside the British.

Ngapuhi Rangitira: astute, diplomatic, misunderstood?

Born c. 1780

Died 1871

Spouse Up to six wives before he became a Christian; his second Christian wife was called Ruth

Children Six children

Early Background

Tāmiti Wāka Nene was born around 1780 into an illustrious family. He was the second son of Tapua, leader and tohunga of the Ngahi Hao hapu. Wāka Nene traced his descent from Rahiri, the founding ancestor of Ngāpuhi. Hone Hene (his enemy during the Northern War) was related to him through the ancestor Kamamu. Nene was from an older generation.

As a young man Wāka Nene developed his skills as a warrior and war leader. During the early 1800s, he fought in battles between factions of Ngāpuhi. He probably took part in the expeditions of the 1820s against iwi to the south, led by the remarkable Hongi Hika who managed to unite the warring factions of Ngāpuhi. However, fighting between Ngāpuhi hapu resumed after Hika died in 1828. The events of these turbulent decades were not forgotten, and deep-seated grievances between certain Ngāpuhi hapu simmered just beneath the surface. In fact, offences caused during the early 1800s may have motivated Wāka Nene to take up arms against Hone Heke in the 1840s.

Attitude towards Europeans

By the late 1820s, Tāmiti Wāka Nene was the highest-ranking chief among his people and one of three leaders in the Hokianga area. With his elevated position came great deal of responsibility. Wāka Nene was quick to recognise the benefits of a European presence. He worked hard to maintain the peace and to protect the Weslyan missionaries and the pakeha traders in his area. The European community came to respect Wāka Nene, and began to rely upon him for advice. In 1839 Wāka Nene was baptised into the Wesleyan faith.

Wāka Nene supported the Treaty of Waitangi, not as a total cession of sovereignty, but as a way of bringing order to the region. Problems associated with European settlement were spiralling out of control, and Wāka Nene could see that something had to be done. During the debate at Waitangi he argued that it was too late for Māori to turn their backs upon the Europeans. His speech must have been persuasive, for Wāka Nene is credited with shifting the mood of the meeting in favour of signing the Treaty.1

Unfortunately, the Treaty did not bring about the positive changes Wāka Nene had predicted. Ngapuhi did not to prosper under British rule and there were many issues which angered the Northern chiefs. Wāka Nene himself was particularly aggravated when the governor attempted to restrict the felling of kauri trees. He threatened to fell a kauri tree in front of the governor to see how he would react. In fact, Nene shared many of the same concerns that drove Heke and Kawiti to take up arms against the Crown.

The Northern War

In July 1844, Hone Heke chopped down the flagstaff at Kororāreka for the fist time. This was a symbolic protest, which reflected Heke’s opinion of the reality of British sovereignty. Although the dissatisfaction was widespread, Ngāpuhi did not unite behind Heke. Plenty of rangatira were angered by Heke’s actions (as of course were the British authorities).

For the remainder of 1844, Wāka Nene worked hard to keep the peace. Wāka Nene assured the Governor that he would keep Heke under control, whilst making it clear that there were legitimate grievances that had to be addressed. Nene’s men guarded the new flagstaff but they did not intervene when Heke chopped it down for a second time in January 1845. However, Wāka Nene was extremely offended by Heke’s fourth attack on the flagstaff and the subsequent destruction of Kororāreka. It was the last straw. Wāka Nene was ready to take up arms against Hone Heke and those who were aligned with him. He explained himself:

"This man [Heke] had … laughed at all our persuasions and threats [we] who are older than himself … I had told the Governor when the first flagstaff was cut down that I would oppose Heke if he persisted in his folly and I am now come to do it.”2

Skirmishing between opposing Ngpāuhi factions started almost immediately and continued on-and-off until peace was declared. These encounters had nothing to do with the British campaigns and did not involve any British troops. By far the most important was the Battle of Te Ahahu in June 1845. Tāmiti Wāka Nene defeated Hone Heke on open ground. Heke was badly injured and was unable to participate in the action for the six months that followed. This was the only outright defeat suffered by “rebel” Ngāpuhi forces during the Northern War.

Wāka Nene and his men did not fully participate in any of the major battles involving the British troops. He provided the British valuable logistical support and plenty of good advice (some of which was ignored). At Ruapekapeka, Nene and his warriors fought off an attack upon the main battery and stockade without assistance from the troops. When the British finally gained entry to the pā, Nene and his men pulled back and left the actual fighting to the British.

Peace

A week after Ruapekapeka, Tāmiti Wāka Nene met with Kawiti and Hone Heke, and they arranged a peace deal. Nene then travelled to Auckland to meet with Governor Grey (Fitzroy’s replacement), and peace was confirmed with the British as well.

Wāka Nene’s motives during the peace negotiations are the subject of bitter words. Many believe that he asked the Governor to confiscate the lands of Heke and Kawiti to be given to him as a reward. Whatever the case, Governor Grey sidestepped a possible political minefield by taking no land in reparations.

Reward

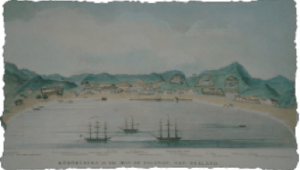

Tāmiti Wāka Nene was rewarded for supporting the Crown. The British built him a cottage at Kororāreka (Russell) and he received an annuity of £100.00 Governor Grey relied upon him for advice, and when Grey was knighted in 1848, Nene was chosen as one of his esquires.

Towards the end of his life, Wāka Nene’s hapu fell into debt due to the declining Hokianga timber trade. However, Nene himself was held in very high esteem by the British authorities until his death in 1871. When he died, Governor Grey wrote in a dispatch to London the Nene “did more than any other [Māori leader] … to establish the Queen’s authority and promote colonisation.”3