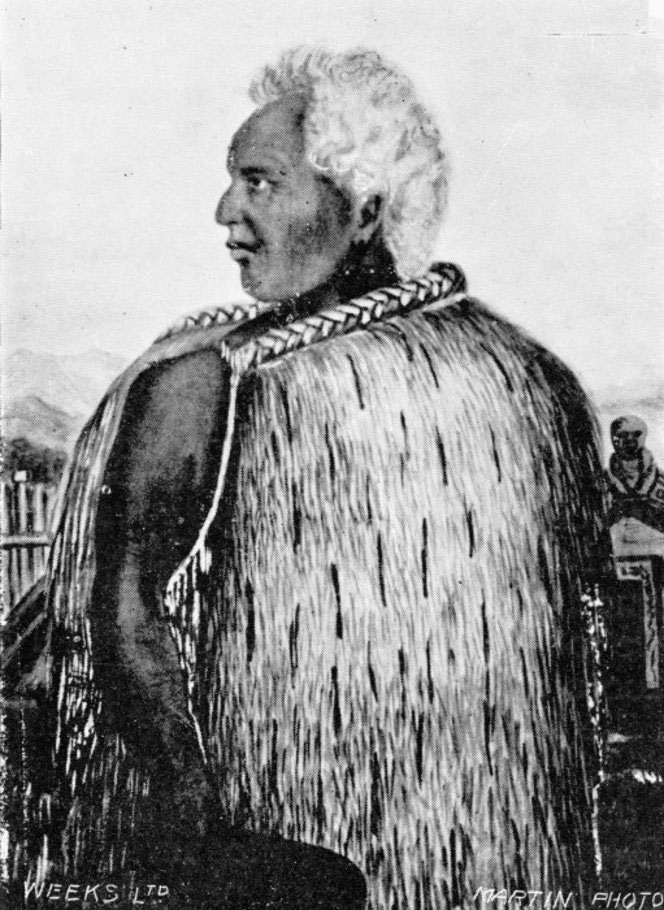

Te Ruki Kawiti

Te Ruki Kawiti was a distinguished leader and great fighting chief of the Ngāti Hine hapu. Kawiti led his people against the British during the Northern War. He was an excellent strategist and tactician, and will forever be remembered as the architect of Ruapekapeka pā.

Ngati Hine Rangitira: distinguished, honourable, talented

Born 1774

Died 5 May 1854

Spouse (1) Kawa (2) Te Tiwha

Children Three sons (Taura, Wiremu Te Poro, and Maihi Paraone Te Kuhanga) with his first wife; one daughter (Tuahine) with his second wife

Early Background

Te Ruki Kawiti was born in Northern New Zealand into an illustrious family. He traced his descent from Nukutawhiti, commander of the legendary Nga-toki-mata-whao-rua canoe, and Rahiri, the founding ancestor of Ngāpuhi. Kawiti was destined to be a great rangātira, and from birth, he was trained in the arts of warfare and leadership. His first wife was Kawa, and she was the mother of his three sons. With his second wife, Te Tiwha, he fathered a daughter.

Kawiti was born only five years after Captain Cook circumnavigated New Zealand. The world of his birth was profoundly different from the world of the Northern War. Kawiti lived through the period of upheaval bought about by early contact, settlement, and colonisation. By 1845, Kawiti was a wise and experienced man past 70 years of age.

Fighting Experience

Kawiti honed his military skills during the so-called Musket Wars of the early 1800s. He took part in notable battles alongside the great Hongi Hika, including Battle of Moremonui where Ngapuhi were defeated by Ngati Whatua. Nearly 20 years later (in 1824) Kawiti joined with other Ngapuhi chiefs and again faced Ngati Whatua in battle, this time emerging victorious. During the Northern War the British were facing a seasoned veteran with a thorough understanding of musket warfare.

Although he was a fierce warrior, Kawiti was not hot-headed. He was a man of integrity and restraint, and over the years, he developed a reputation as a peace-maker. For example, his diplomatic efforts prevented the “Girls’ War” of 1830 from becoming a full-scale confrontation between Ngapuhi and the people of Kororāreka.

Kawiti and the Te Tiriti

At Waitangi in February 1840 Kawiti argued against a treaty with the English. He spoke of wanting to retain his lands, and his concerns about British soldiers arriving to enforce the Governor's words. He finally did sign the Māori version in May that year after his people persuaded him to do so. Kawiti added his name at the top of the document above all of the other signatures, as befitted his rank.

Kawiti’s initial reservations about Te Tiriti proved to be correct. In 1845, he received a message from Hone Heke (the son-in-law of the late Hongi Hika). Heke sent to Kawiti a beautiful greenstone mere smeared with human excrement. This was no ordinary weapon. It was a named taonga with great mana, handed down from Hongi Hika. The message was clear: Ngāpuhi mana, honour, and authority had been trampled by the British. Heke was asking for help, and Kawiti agreed to join with him.

The War in the North

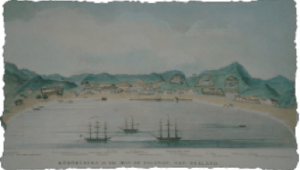

On 11 March 1845, Kawiti and his men attacked the group of British sailors guarding the town of Kororāreka. Their intention was to create a diversion, to allow Heke to cut down the Maiki Hill flagstaff for the fourth time. Heke and Kawiti, together with a Te Kapotai contingent, successfully engaged all three British military positions.

A few months after Kororāreka, Kawiti went to reinforce Hone Heke at his pā on the shores of Lake Omapere. When the British attacked the pā, they faced a co-ordinated response. Kawiti’s role was to engage the British from outside the pā while Heke provided support from within. The tactic was successful in that the British were eventually forced to withdraw, but it came at a very high cost. Kawiti lost too many men, and he never again engaged the British in open combat.

After the battle at Lake Omapere, Kawiti and Heke went to a pā at Ohaeawai belonging to their friend Pene Taui. The chiefs worked together to strengthen the pā in anticipation of another attack. In mid-June Heke was defeated and badly injured by Tāmiti Wāka Nene, so the defence of Ohaeawai was left in the capable hands of Kawiti and Taui. The British suffered a terrible defeat, displaying their arrogance and their failure to appreciate Kawiti’s military prowess. Despite this victory, Heke’s resolve began to waver and he started to think about making peace with the British. Kawiti encouraged him with these words:

“I warned you that the water was too deep for you alone to net the big fish, but you would not listen. Now the water just barely reaches your knees and you cry, enough!”1

At the end of 1845, Kawiti stood up against the British once again. Ruapekapeka was his masterpiece, a culmination of his wisdom and expertise. The outcome of the battle was inconclusive, although the British were quick to claim a great victory. Kawiti himself was inside the pā when the soldiers entered but most of his warriors were not. They may have been setting up defences at the rear. Once the fighting began Kawit’s men were quick to escort him away from the pā – they couldn’t risk their rangatira falling into the hands of the British.

After the Battle of Ruapekapeka Kawiti and Heke arranged to meet with Tāmati Wāka Nene, the leader of the Ngapuhi who had supported the British. They talked of peace, and afterwards Nene met with Governor Grey to propose an end to the fighting. Grey released a formal proclamation of peace on 23 January 1846.

Later Years

Kawiti lived out his later years in peace and died at Waimio an old man. His remains were placed with those of his ancestors in Te Pouaka-a-Hineamaru. His tangi, period of mourning, lasted a year. His son Maihi succeeded him as the leader of Ngati Hine, and it was Maihi who arranged for the Kororāreka flagstaff to be re-erected.