A Brilliant Success?

Soon after the battle, Heke and Kawiti met with Tāmiti Wāka Nene and his companions. All agreed that the time to fight had ended. In the words of Kawiti “peace shall be made with the Governor, and peace shall be made with Nene.” Heke and Kawiti reached out to Governor Grey with Nene acting as an intermediary. On 23 January, Grey issued a formal proclamation granting a “full pardon” to all of those involved in the “rebellion”. The Northern War was officially over.

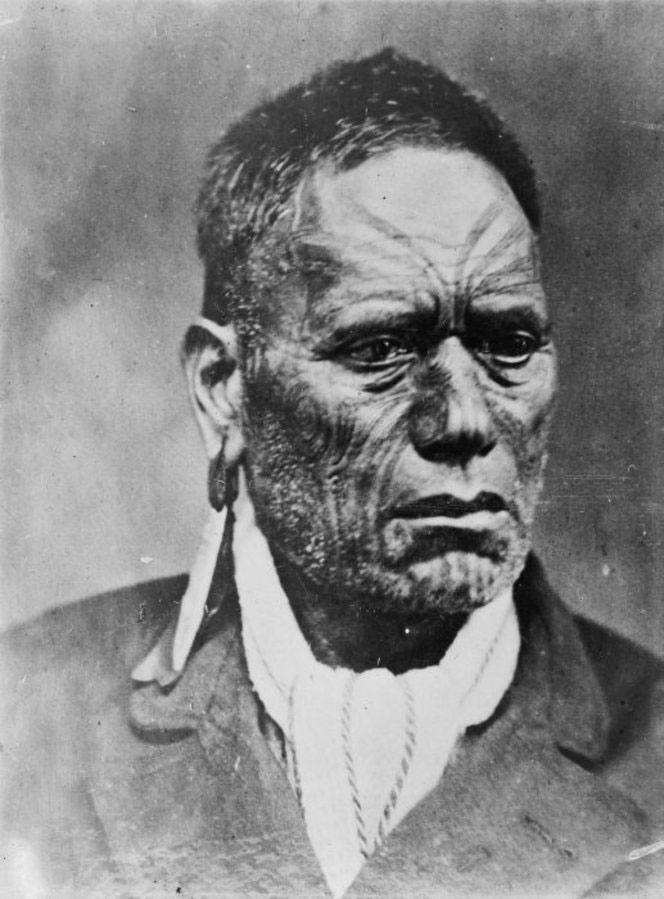

Maihi Paraone Kawiti

Photographer unknown. From the Alexander Turnbull Library ref. 1/2-075214-F

Despard and Grey announced that Ruapekapeka had been “taken by assault” and that the outcome was a “brilliant success” for the British. According to the official despatches, the rebels had been thoroughly beaten and dispersed. In the months that followed, Grey took on a magnanimous persona, announcing pardons and arguing against the confiscation of lands.

“... anyone to read Despard’s despatches would think that we had thrashed the natives soundly whereas really they have had the best of us on several occasions. I really begin to think that it is perhaps all a mistake about us beating the French at Waterloo. I shall always for the rest of my life be caution how I believe an account of a battle.”

F. E. Manning, settler, 1846

The official accounts have Heke and Kawiti humiliated, Ngāpuhi broken and defeated. This was not the case, as Grey's actions – if not his words – confirm. Grey’s unconditional pardons and the lack of land confiscation contradicted his pre-battle statements about the need to crush Heke and Kawiti once and for all. His about-face was not motivated by kindness and generosity, although he couched it in those terms.

“The flagstaff in the Bay is still prostrate, and the natives here rule. These are humiliating facts to the proud Englishman, many of whom thought they could govern by a mere name.”

Henry Williams, 1846

Grey was clever enough to realise that land was a very delicate issue and that to confiscate any would cause ongoing unrest. He had other things to worry about. Trouble was brewing with Ngāti Toa in the Wellington region over disputed land purchases. The last thing Grey wanted was a general Māori uprising. Soldiers were sent to deal with the Wellington issues (with limited success), and Heke and Kawiti lived out the rest of their lives free from British interference.

Grey’s claims to have broken and humiliated Heke were completely false. Heke’s mana and authority increased after the war ended and he certainly had no reason to feel humiliated. Together with Kawiti, he had fought with valour against an enemy with massive technological and numerical advantages. There had been no rout, as the flagstaff lying prone bore witness.

Grey made no attempt to re-erect the Kororāreka flagstaff. At the time, he was praised for his wisdom and kindness, for not rubbing salt into the wounds of his humiliated enemies. The truth is he didn’t really have much choice the matter. If the symbol of British sovereignty was again cut down, he’d be honour-bound to do something about it. The government simply couldn’t afford for the fighting in the north to resume.

In January 1858 Maihi Paraone Kawiti, the son of Te Rukki, erected a new flagstaff above Kororāreka. It was 95 feet long and two feet thick, and it took hundreds of men to carry it up Maiki Hill. The operation was planned, paid for, and carried out entirely by Māori who had fought against the Crown. The government was ambivalent about the idea, still worried that any flagstaff atop that hill would attract trouble. They needn’t have worried, because the new flagstaff had a different meaning: it symbolised reconciliation and unity in the aftermath of the Northern War. The flagstaff is called Te Whakakotahitanga and it stands on Maiki Hill to this day.