Kororāreka destroyed

(11 March 1845)

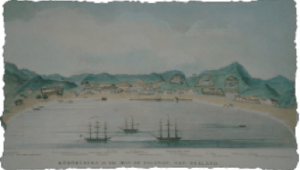

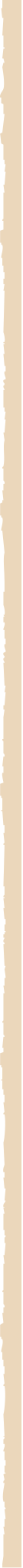

In 1844, the town of Kororāreka was a lively trading post and port, still the fifth largest town in the colony despite a recent decline. The cottages of the pākehā settlers sat next to thatched Māori whare, nestled below steep hills covered in mānuka and fern. Whale ships frequented the bay, and their crews frequented the public houses ashore. The flagstaff – the symbol of British sovereignty, which attracted Heke’s wrath – stood high above the village on Maiki Hill.

Kororāreka on 10 March 1845, the day before it was destroyed. The ships are the Hazard, the Victoria and the Matilda.

By G. T. Clayton. From the Alexander Turnbull Library ref. C-010-022

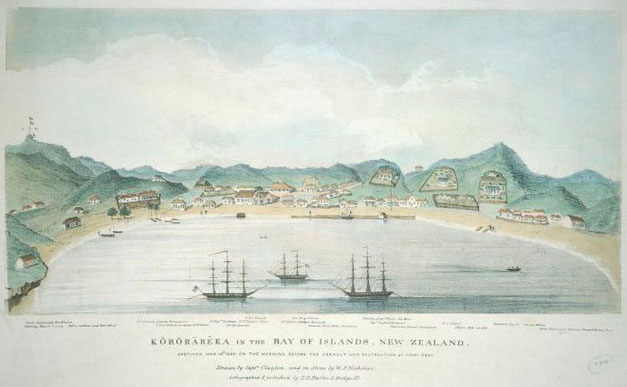

The monument in Russell cemetery to the British sailors killed during the destruction of Kororāreka.

From the Alexander Turnbull Library ref. PUBL-0163-1891-001

At sunset on 11 March 1845, the town was a smouldering ruin. The destruction of the town was a consequence of Heke’s fourth and final attack on the flagstaff atop Maiki Hill. A well-organised force of Ngāpuhi and Ngāti Hine warriors attacked in three groups. The overall objective was simple: to cut down the flagstaff again. The intention wasn’t to harm the township itself, nor the civilians who lived there.

The action began before dawn when Kawiti’s taua attacked the armed marines and sailors of the HMS Hazard who were stationed ashore. The attack was a diversion, and it worked perfectly. Heke captured the flagstaff and blockhouse while the soldiers were distracted by the action below. Heke and his men killed the few soldiers who remained within the blockhouse and set to work upon the flagstaff.

The remaining soldiers in the village gathered hastily at the barracks, but they were engaged by another group of warriors from Ngāti Manu and Te Kapotai. Historian Ralph Johnson explains: “... the three divisions of Ngāpuhi attackers were deployed in such a way as to first surprise the flagstaff defences, and then to engage each of the three British military positions (the blockhouse, the lower blockhouse, and the single gun battery). There was no attempt made at this or any later stage to attack the town or residents.”1

It took hours to cut down the flagstaff because the lower section was sheathed in iron. Meanwhile, Captain Robertson and his men were fighting Kawiti and his Ngāti Hine warriors at the southern end of the bay. It was a brutal hand-to-hand engagement with many casualties on both sides. The attack lasted just long enough for Heke to achieve his objective. Once the flagstaff fell at about 10 am, all three groups withdrew. At lunchtime, Heke and his supports flew white flags to declare a truce.

Despite the ceasefire, the British officers feared that Heke and Kawiti intended to attack the town itself. They ordered the evacuation of pākehā civilians to the ships anchored in the bay. The Ngāpuhi warriors watched from the hills without attempting to intervene. When most of the civilians were safe aboard the ships, the town’s powder magazine exploded. Historians have debated whether it was a careless accident or a deliberate detonation to prevent the enemy from gaining possession. Whatever the case, the remaining troops withdrew from the town shortly after the explosion. In the aftermath, the commanding officers were to face criticism for abandoning the town too early and too easily.

Bishop Selwyn, who was present at the time, said, “there is no evidence of any general or indiscriminate hatred of the natives towards the English settlers or any disposition to bloodthirsty or savage acts of violence.”2 However, the property within the abandoned township was considered fair game. Some of the warriors started to plunder, but Heke and Kawiti agreed to allow the settlers back ashore to gather some of their belongings. At this inopportune moment, the HMS Hazard began to fire shots into the town for reasons, which are not entirely clear. The apparent act of aggression infuriated the Ngāpuhi warriors. Andrew Bliss, master of the whaleship Matilda summed up the situation:

...it is my decided opinion, that had those shots not been fired, the Town might have been saved from plunder and destruction ... shortly after our arrival back on board, they commenced plundering in every direction, and fired the town.3

By the end of it, Kororāreka lay in ruin and around thirty men were dead. Each side probably suffered about the same number of casualties, many of which occurred at the beginning when flagstaff was taken. Heke arranged for the British dead to be given to the missionary Henry Williams for a decent burial. The loss of the town was a serious blow, and the colonial government attributed all of the blame to Heke, Kawiti and company. The government ordered a full-scale military offensive, thus beginning the Northern War.

3 cited in Johnson 2006: 198-9