Small Arms

People writing about the Battle of Ruapekapeka have focussed upon on the heavy artillery. The artillery certainly damaged the structure of the pā, but most of the deaths and injuries were at close quarters caused by a range of hand-held weapons.

Close-up of a Percussion Tupara musket lock

Photo: J Osborne

Photo: Department of Conservation

Close-up of a Percussion musket P1839

Photo: J Osborne

Close-up of a Percussion musket P1839 lock

Photos: J Osborne

Phil Cregeen firing a flintlock musket at Ruapekapeka.

Photo: Department of Conservation

Close-up of a Flintlock musket P1797

Photo: J Osborne

Close-up of a Flintlock musket P1797 lock

Photo: J Osborne

Close-up of a Percussion Tupara musket

Photo: J Osborne

Close-up of a Percussion Tupara musket lock

Photo: J Osborne

Unfortunately we don’t have a great deal of specific information about the small arms in use on Sunday 11 January, when the soldiers entered the pā. There were certainly muskets and bayonets, probably double-barrelled shotguns, and perhaps pistols, swords, and traditional hand-held weapons such as patu.

Muskets and bayonets

The 1840s were a transitional period in terms of firearms technology. The long reign of the flint-lock musket drawing to an end, and percussion-cap mechanisms were coming to the fore. The British Army started to issue percussion-cap muskets in 1839. The new mechanism had several advantages over the flint-lock variety: it was much more reliable and there wasn’t a flint to wear out after twenty or so shots.

Although percussion-cap muskets were clearly superior to the flint-lock variety, the rate-of-fire was still very slow. The soldier was desperately vulnerable while reloading. At close quarters muskets of any kind were of limited use.

When it came to hand-to-hand fighting, the British had a significant advantage over their Māori opponents. The troops had bayonets whereas the Māori generally did not,1 instead using hatchets or traditional club-like weapons. A bayonet basically converts a musket into a spear, allowing the soldier to slash and stab at their opponent from a greater distance. The bayonets in use during this time period were of the “socket” variety, where the blade is set into a tube which fits over the barrel of the gun.2

The musket most commonly available to Ngāpuhi was the famous “Brown Bess".3 These were muzzle-loading smooth-bore muskets, issued by the British Army or based on the same design. The Brown Bess muskets in Ngāpuhi hands were of the flint-lock variety.

They were originally fitted with a goose neck cock, but many of them snapped off through the neck and were replaced with a reinforced neck ring cock as shown. The triangular socket bayonet was held in place by a spring lever pressing against the foresight.4

In a nutshell, this is how flintlock muskets work: a shower of sparks is generated when the flint hits the frizzen, a hinged steel cover on top of the pan which is filled with powder. The power ignites, the flash passes through a vent to the combustion chamber, igniting the main powder charge, and firing the gun. Loading a flintlock musket was time-consuming, and an average soldier could be expected to fire only once or twice per minute.5

The defenders inside the pā were armed with flint-lock muskets and double-barrelled shot guns. Flint-lock muskets had been the weapon of choice for European armies for several centuries, and in the early 1800s Ngāpuhi began trading for muskets with great enthusiasm. By 1845 Ngāpuhi had plenty of muskets, and decades of experience using them in battle.

Flint-lock muskets were not particularly accurate, best used at ranges less than 50 – 70 yards (45 – 65 metres). Nor were they very reliable: the barrel tended to clog up, the powder got damp easily, and the flints began to wear out after about 20 shots.6 Kawiti’s men at Ruapekapeka did have problems with range, as reported by Major Cyprian Bridge in his diary:

“… the enemy had opened a hot fire of musketry on [the main camp], but from the distance his no one. Most of their shots fell short, except some rifle balls which whizzed over our heads…”

Major Cyprian Bridge, diary entry for 30 December 1846

The muskets belonging to Kawiti’s men may not have been the best quality in the first place: there was a difference between military issue “Tower” muskets and cheap “trade” muskets. Tower muskets were tested by government inspectors at the Tower of London, and although trade muskets were meant to be checked at commercial proof-houses, the quality was often dubious.7 We don’t know whether Kawiti’s men were armed with Tower muskets or trade muskets. It seems likely that they had some of each.

As well as flint-lock muskets, Ngāpuhi were in possession of double-barrelled shotguns known as tupara. These guns were loaded musket-balls, and so did not resemble modern shotguns which fire many small pellets. Percussion Tupara were double-barrelled muskets introduced c1835.

Kawiti’s men at Ruapekapeka may actually have had more tupara than they did muskets. In late 1845, Governor Grey wrote the following about “the enemy”:

“Their arms are generally a double barrelled shotgun, sometimes a musket without a bayonet, and a hatchet for close quarters, but which is a useless weapon when opposed to bayonets … They invariably carry two of three pouches filled with cartridges, they put a larger charge of powder in their cartridges than Europeans use, and the guns consequently carry further than the muskets of the British Soldiers. They are at present abundantly supplied with arms and ammunition.”

Memorandum, G. Grey, 6 December 1845

Tupara were not very accurate but at close quarters they were absolutely deadly. There was a bloody demonstration of this fact during the Battle of Ohaeawai in mid-1845. The defenders were armed with double barrelled shot guns8 and safely hidden behind the palisades. They opened fire upon the charging British troops, their musket balls scything through the mass of bodies at almost point-blank range. We don’t know to what extent the defenders used tupara during the Battle of Ruapekapeka, as opposed to single-barrelled “Brown Bess” muskets.

See also: Brown Bess Muskets (PDF, 1,049K); NZAR 362 Sword HEIC Naval Officers (PDF, 337K)

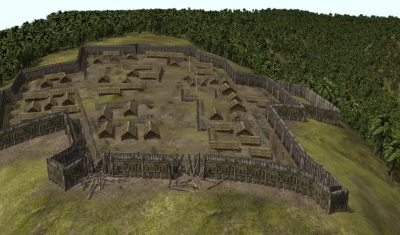

Heavy Artillery versus Timber and Earth

It can be difficult for modern readers to grasp the scale of the bombardment of Ruapekapeka Pā. In context, the British had an enormous amount of firepower at their disposal. This was their third campaign inland against pā belonging to their Ngāpuhi enemies. During the Battle of Puketutu, the British hit Te Kahika Pā with one Congreve rocket (out of 12 that were fired). And that was the extent of the bombardment. After failing miserably at Puketutu the British adjusted their strategy to focus upon the use of artillery. At Ohaeawai soldiers bought with them two brass 6 pounders and two 12 pounder carronades, but it soon became apparent that the guns were not big enough to breach the defence. Colonel Despard sent for a 32-pounder cannon, which arrived a week later. It was big enough. If only he’d possessed a modicum of patience the outcome of the Battle of Ohaeawai may have been different.

Ohaeawai Pā and Ruapekapeka Pā were strong fortifications, well designed and solidly built. But they were constructed of timber and earth. No matter how well designed, a timber palisade cannot withstand concerted bombardment from 32-pounder cannon. At Puketutu and again at Ohaeawai the British were surprised by the strength of the outer defences. At Ruapekapeka they knew what to expect, and so they bought with them sufficient firepower to achieve their objective. Finally, the British had realised what it took to knock down a Maori pā.

2 H. Despard. 1846. Narrative of an Expedition into the Interior of New Zealand.

3 Osborne, J. 2007. Brown Bess Muskets. Unpublished Report.

4 Image and description courtesy of John Osborne.

5 P. D’Arcy. 2000. Maori and Muskets from a Pan-Polynesian perspective. New Zealand Journal of History 34:117-132

6 Photo and description courtesy of John Osborne.